- Home

- Carrie Mac

Beckoners

Beckoners Read online

the beckoners

carrie mac

Text copyright © 2004 Carrie Mac

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher.

National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data

Mac, Carrie, 1975-

The beckoners / Carrie Mac.

Electronic Monograph

Issued also in print format.

ISBN 9781551434377(pdf) -- ISBN 9781554697304 (epub)

I. Title.

PS8625.C3B43 2004 jC813’.6 C2004-903706-4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2004108679

Summary: When Zoe moves to a new town, she finds the line between victim and tormentor is easily crossed.

Orca Book Publishers gratefully acknowledges the support for its publishing programs pro-vided by the following agencies: the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP), the Canada Council for the Arts, and the British Columbia Arts Council.

The author would also like to thank the Canada Council for their generous support during the writing of this book.

Design and typesetting: John van der Woude

Cover Artwork: Getty Images

In Canada:

Orca Book Publishers

PO Box 5626, Station B

Victoria, BC Canada

V8R 6S4

In the United States:

Orca Book Publishers

PO Box 468

Custer, WA USA

98240-0468

www.orcabook.com

08 07 06 05 04 • 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Sam, of course—

because without her (and the outfits)

I would not have survived adolescence at all.

prologue

They had called her Dog for years already, since kindergarten. Back then she’d come to school every day with a black felt tail pinned to the bum of her pants and floppy ears glued to a headband. When she was five, she wanted to be a dog more than anything. That’s when Shadow was just a puppy, a small tumbly thing stumbling over his big paws as he followed her to school, where he whined all day by the fence, waiting for her. When April was five, she loved being called Dog. When she was five, she was popular. All the kids wanted a dog just like Shadow, a dog that never left your side, a dog that would save you from drowning, a dog that would sleep with you every night, his drooly black head on the pillow beside yours. All the kids wanted to be her friend because of Shadow.

Not anymore. At fourteen, kids were just as likely to call her Bitch, which just naturally progressed out of Dog. They were chanting Dog, though, the day the fire alarm went off during lunch.

Beck shoved April onto her knees as soon as Mr. Cromwell disappeared around the side of the school to find out what was going on and where all the other teachers were. Lindsay held April’s arms behind her back, pulling them so tight April thought her collarbone might crack.

“Dog! Dog! Dog!” Half the school crowded her, screaming at her.

Heather pulled a box of dog treats out of her backpack and forced the first one into April’s mouth. April had no choice but to chew and swallow; Lindsay was there to bash her face in if she didn’t. Heather, Beck, Janika and Jazz all took turns forcing the chalky biscuits down April’s throat while the crowd counted.

“Sixteen!”

“Seventeen!”

“She likes them!” Beck hollered. “She used to have them in her lunchbox every day!” That was true, but they were cookies her mom made, shaped like doggie treats because that’s how April wanted them, just like Shadow’s.

“Twenty!”

“Twenty-one!”

April’s throat constricted, but she didn’t throw up, not until the box was empty, the crowd had scattered and she was halfway back to class. She threw up in the middle of the hall, outside English. As she retched, someone kicked a garbage can towards her, so she puked in that. She’d eaten the whole box. Fifty-two liver-flavored dog biscuits shaped like bones, and the crumbs at the bottom too.

At five, she prayed to God that she would wake up one day and be a real dog just like Shadow. At fourteen, she prayed to God she’d never wake up at all.

zoe

Once again, it was Zoe who got Cassy up. That little brat started screaming her head off just past dawn, jumping around in her crib so it banged against Zoe’s bedroom wall, hollering her head off, cheeks red, face covered in snot, and Alice was just across the hall, both doors open, fast asleep? Zoe did not believe her mother could sleep through that. It’s humanly impossible. She pretended to, just so Zoe would get up and do it, and then Alice would wander down hours later, when it was too hot to sleep anyway. She’d run her fingers through her hair, yawning while she talked, saying things like, “Oh, what time did you and Cassy get up?” or “Aw, thanks hon, I was so tired last night I would’ve slept through a terrorist attack.” Alice thought that was funny. Zoe did not.

Cassy screamed even harder when Zoe came into the room that morning. When she did that, Zoe wanted to smack her. Instead, she poked Cassy’s belly hard.

“Shut up!”

Her baby sister, half-sister if she was being specific, did shut up. She hiccupped back a great big sob and stretched out her arms to be picked up by her fifteen-year-old fairy princess, her Zo-Zo, who she loved best in the world, after Alice mostly, but not always, sometimes even more than Alice.

Alice knew exactly how to make a bad day even worse. She eventually did get up, just as Zoe was about to take Cassy upstairs and dump her on her, asleep or not. She shuffled around in the kitchen for a while, opening and closing cupboards while Zoe made a great production of leaving. Then when she was halfway down the block, Alice rushed out of the house after her, barefoot, housecoat flapping, tits bouncing under her slip, Cassy pinned under one arm.

“Wait, hon! Come back a minute!”

“I don’t have a minute.”

“Sure you do.” She pulled Zoe back towards the house. “It’ll just take a sec.”

She steered Zoe into a chair at the kitchen table, in front of a mug of hot lemon tea. Alice sat across from her, fixing her with that honey-I’m-so-sorry look, and inched the sugar in her direction.

“It’s too hot for tea.” Zoe pushed the sugar back at her.

“I would’ve made iced tea, but I wanted to catch you before you left.”

“You didn’t. I’d already left. You know, you could just tell me you want to talk. We don’t have to do this every time.” Zoe pushed the mug of tea away too. “Can you get on with it? I’m going to be late.”

“Okay. All right. Here’s the thing.” Alice took a sip from her own mug of black coffee. “I got offered a promotion, to manager of the homeless shelter—”

“That’s great, Mom! When do—”

“—in Abbotsford, Zoe.”

Zoe stared at Alice. Alice stared at the crack on her mug. Outside, the ice cream truck passed on its first round of the day, its looping jingle drawing Cassy to the front door.

“You took it, didn’t you?” Zoe pushed her chair back and stood, hands on hips. “You took the job and you never told me? You never even asked what the hell I think about it?”

“Hold on, Zoe, let’s talk this out.”

“What’s there to talk out, huh? If I say I’m sick and tired of moving and want to stay here just TWO MORE YEARS, just until I finish school, would you change your mind?”

“No. I won’t lie to you about that.”

Zoe hated it when Alice said that, like she was doing Zoe some kind of favor. Like she was all high-an

d-mighty making some kind of sacrifice by telling the truth.

“I’m going to work now, do you mind?”

“You don’t have anything else you want to say about this?”

“Umm, lemmee see.” Zoe cocked her head to the side and put a finger to her chin. “Gee, thanks for all that childhood stability, Mom. I’m sure it’ll help me develop into a normal, healthy young adult with great self-esteem.”

“Sarcasm isn’t helpful, Zoe.”

“Yeah, well, neither are you.” Zoe slammed out the door, even though it’d been open all night because of the heat. She flounced down the sidewalk to find Cassy standing in the middle of the street, waving at the ice cream truck. It idled in front of her, the driver shaking his head in disgust. Behind the toddler, a mini-van full of mothers and children dressed for a day at the lake were just about to pull over and take charge. Zoe narrowed her eyes at the prim-lipped women. She picked Cassy up and dumped her over the fence, hollering at the house, “Come get your kid before the Dickie Dee man runs her over!”

The woman driving the van leaned out her window and curled a finger at Zoe. Zoe held up a hand.

“Save it, lady,” she said and then took off through the neighbor’s driveway to the alley.

When Zoe came home between the matinees, Alice was taking lasagna out of the oven, face glistening with sweat, a fan set up on either end of the counter, churning the hot stale air.

“You think making my favorite meal will just magically make it all better?”

“Honey—”

“Because it won’t.” Cassy pulled at Zoe’s Movieville-issue shorts with chocolate-batter hands. Zoe picked her up and carried her to the sink, holding her away from the stupid yellow shirt with the film reel on the back. She rinsed Cassy’s hands under the tap. “Brownies, too? If you feel this bad maybe it means you’re doing something wrong. Did you ever think about that? That maybe you made a mistake?”

“It’s not a mistake.” Alice wiped her brow with an oven mitt. “Look, I’m sorry you’re taking it so hard, but—”

“How else am I supposed to take it?”

“As an opportunity for positive change, Zoe.”

That, right there, was Alice Diane Anderson’s answer to everything since she’d started borrowing self-help tapes from the library. You cut your leg off with a chainsaw? Hell, that’s no biggie, look at it as an opportunity for positive change! Your child was kidnapped and raped by the vacuum salesman? Well, gosh, let’s not say she’s scarred for life; let’s say she’s been given the opportunity for positive change! Oh, he left her dead in a ditch? Well then it’s your opportunity for positive change, isn’t it?

The only positive thing Zoe could conceive about moving, and she would never tell Alice this, she wouldn’t want to give her the satisfaction, is that she would be glad to see the assend of Prince George. If Vancouver was Hollywood North, with its cappuccino and production studios, its sea-wall dotted with celebrities, the ocean breeze washing the city with slick, fresh appeal, then Prince George was the capital of lame home movies shown on stained white sheets tacked to basement fake-wood paneling, grainy shots of naked babies waving in bathtubs and humiliating slices of school plays.

Prince George was full of 4X4-ing, hockey addicted, sweat-drenched guys whose sole goal in life was to get on at the mill and save up for a big screen TV. And their girlfriends, we can’t forget about those skanks, with their biffed-up hair and skin-tight jeans and high heels and Budweiser tank tops. Zoe’s Prince George littermates wouldn’t know there was any different way of being, even if they were abducted by aliens in the middle of one of their bush parties and deposited, alone, in various cities all over the world. They’d just sit on the curb, light a cigarette or roll a joint and wait for their beer-guzzling buddies to show up to drive them to the rink.

On the other hand, Zoe had been fully prepared to stick it out there until she graduated, although since Luisa went back to Brazil, she was friendless again. The summers were always like that. The next exchange student wouldn’t come until September. Zoe was already looking forward to that. Before Luisa, Milo and Jane down the street had sponsored Natasha from Russia, and before her, Perseverance from Haiti. Zoe counted on their supply of exotic girls from far-off places to fill the rotating role of Zoe’s Best Friend, otherwise she would never have any friends at all.

The way Zoe looked at it, all the lamevilles she’d ever lived in were material for her to use later, not that she intended to make movies about dumpy towns in the middle of nowhere, but enduring them, that would make her a better filmmaker. Every creative genius had a shitty childhood they grew up to exploit, right?

This would be, let’s see...Kamloops, Trail, Vernon, Grand Forks, Lethbridge—if you count that three month “This is it, Zoe, he’s so good to us and I’m totally in love” disaster— Kelowna, Williams Lake, Prince George and now Abbotsford. Nine moves in fifteen years, and not one of them to anywhere half decent. Was that fair?

Oh, but wait, we all know what Alice would say to that.

“Whoever said life was fair, Zoe? Did I ever say life was fair? Now I know I’ve said a lot of things about life, but I never said it was fair, did I?” No, she never did, but that didn’t mean she was right. It just meant she knew how to rework tired old parental clichés.

moving day

For Zoe and Alice, moving day normally looked like this: Alice screaming at Zoe from inside the U-haul, did you pack this or that and do you know where the whatsit is and could you bloody well hurry it up ‘cuz we don’t have all day, you know? And Zoe, running up and down the walk with boxes and chairs and lamps and suitcases and black garbage bags full of stuff they ran out of time to pack properly. They always left a whole pile at the end of the driveway with a Free sign, either because they ran out of time, or they ran out of room, or it was junk they didn’t want anymore anyway.

This move was different. The Fraser Valley Regional Homeless Shelter and Housing Resource Society, thankfully called Fraser House by most, was paying for the move. Alice and Zoe just lounged in their bathing suits and sunglasses on towels on the front lawn, lathered in suntan lotion. Zoe guzzled back lemonade in the dry heat, while Alice sipped hers, generously spiked with mint schnapps. All they had to do was pick up lunch for the road and make sure Cassy didn’t end up packed in a crate. She was determined to help. She’d hooked her beloved purple plastic dinosaur cup on one thumb and was pushing boxes down the hall three times as big as her, grunting and muttering, “Cassy do it, Cassy do it,” until one of the movers gave her the job of sitting on a stool beside the door holding a “very important” empty tape gun.

Just as the three of them were about to leave, Harris drove up, his beat-up truck clunking so loud they heard him long before they saw him.

Alice pulled her sunglasses down briefly. “Here we go,” she muttered under her breath. “Prepare for a scene.”

Harris had come over late the night before, after Zoe had finally finished packing and had gone to bed. She’d been asleep, but his truck woke her up. He and Alice had talked in the kitchen with the door closed, their voices starting out all hushed and civilized and then getting louder and louder until they were screaming at each other like afternoon talk show trash.

He was all, “What the hell makes you think you can just up and take off with my little girl?”

And Alice was all, “You knew damn well when we got into this that I wasn’t making you no promises! You didn’t even want her in the first place, and now it’s breaking your heart to see her go? You think I’m some kind of idiot? You think I’m that stupid?”

There was a dangerous pause, and then something, it sounded like a beer bottle, smashed onto the tiles. Harris hollered at Alice that he’d see her in court; she hollered back at him that if he was that organized she’d be damned surprised, and then he slammed out the back door so hard it bounced back on its springs three times.

The next morning, he’d switched to a different tactic— begging, complet

e with a dozen yellow roses, a little wilted from the heat.

“Alice?” he hollered from his truck. “Alice!” The movers squinted into the sun at him. Harris scowled at them. “What the hell you looking at?”

Alice shook her head. “You, you stupid idiot!”

Harris’s mouth gawped open, like he was going to tear into Alice for that. Zoe could almost see him reeling in the nasties, as if they were on fishing line, until all he said was, “Don’t I even get a chance to change your mind?”

“No, you do not, Harris Kellerman!”

Harris knocked his forehead against the steering wheel a couple of times before getting out and marching over. He must’ve done the night shift after their fight; he reeked of the cannery, fish and sweat. He thrust the roses at her. “I’m just asking you to reconsider, Alice. Please?”

“No.” Alice set the roses on the grass beside her.

“Come on, baby. Please? Think about it? Humor me? At least keep it in mind?”

“Keep what in mind?” Zoe asked.

“It doesn’t matter, Zoe.” Alice sighed. “Harris, we’ve been through this a hundred times, and this is just the way it is. See that?” She pointed to the moving truck. “That’s going to drive all our things to Abbotsford. And see that?” She pointed to the orange station wagon, with its bashed-in side and mismatched hood. “That’s going to take my little family to Abbotsford. My little family: Zoe, Cassy and me.”

“That’s not fair, Alice.” Harris put a hand above his eyes, shielding the sun.

Zoe looked at Alice, eyebrows raised, waiting for her to give him the whoever-said-life-was-fair line. Alice just stared at him, waiting for him to get on with it.

“There’s nothing I can say? Nothing I can do?”

Alice shook her head.

“Alice.” He pointed a nicotine-stained finger at her. “You’re one hell of a hard woman, you know that?”

“It’s a free country.” Alice shrugged. “Think whatever you want.”

Wildfire

Wildfire The Opposite Of Tidy

The Opposite Of Tidy Beckoners

Beckoners 10 Things I Can See from Here

10 Things I Can See from Here The Gryphon Project

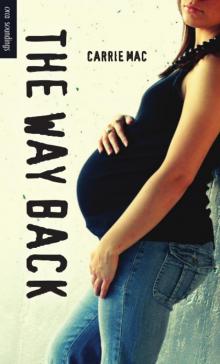

The Gryphon Project The Way Back

The Way Back Pain & Wastings

Pain & Wastings